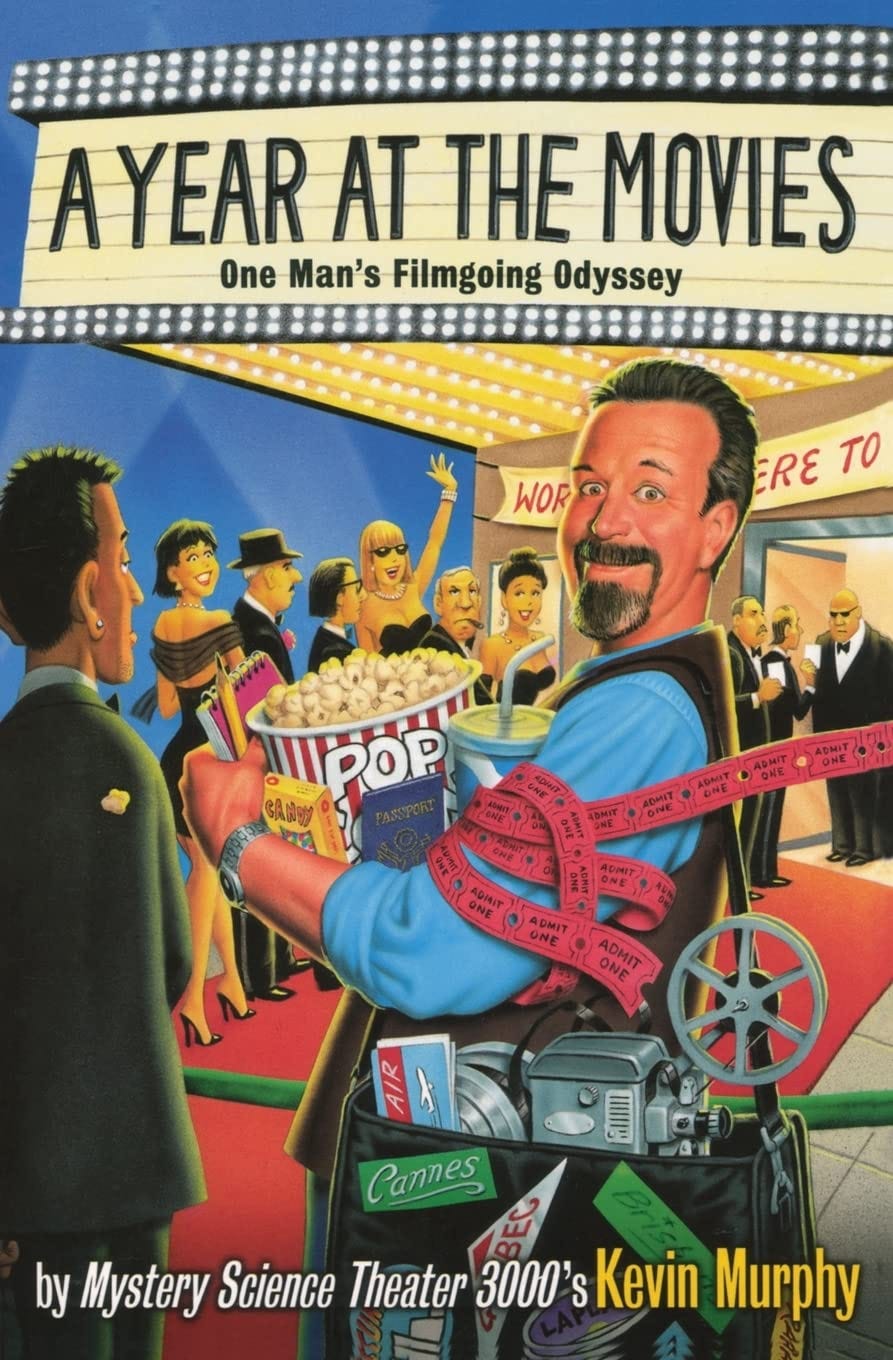

Dial around your radio and you’ll sometimes hear a station’s tagline: “The best music of the ‘80s, ‘90s, and today!” Then it dawns on you that it has been “today” for twenty-four years. You are not crazy and you aren’t in some purgatorial Groundhog Day scenario. You are in purgatory but we call it by another name: Post Pop-Culture Ground Zero 1997. You can find detailed descriptions of it from maverick Gen-Y authors such as Brian Niemeier, JD Cowan, and David V. Stewart, but the short version is that 1997 was the year when most entertainment ceased to be creative and started being vapid consumer products. So you are not alone in this wasteland. In fact, even a boomer like Kevin Murphy (of Mystery Science Theater 3000 fame) noticed something was amiss way back in 2002 with his book, A Year at the Movies: One Man’s Filmgoing Odyssey.

Kevin embarked on a wild experiment for his book. “Beginning tomorrow, January 1, 2001, I, Kevin Murphy, promise to go to a theater and watch a movie every single day, for an entire year.” What follows is a diary of the theaters visited, the movies watched, and plenty of commentary about the experiment and the state of the modern moviegoing experience. While his film tastes are decidedly boomer, such as his admiration for awful Lasse Hallström films, his experiment implicitly shows that driving to a theater, loading up on salty and sweet snacks, sitting in a dark room and having images beamed into your eyeballs is (or was) a ritual.

I was a servant of this ritual. My first job ever was as a polyester-vested usher for my local movie theater. This was the glorious ‘80s when the stars gleamed, the action thrilled, and the sacrament of popcorn was still valid, being confected with proper matter: coconut oil. The duties of an usher were very light once the films got rolling, so to kill the time you watched the movies. Many, many times. The result is that movies such as Back to the Future, Aliens, and Highlander are fully imprinted in my memory. The longer the time a film spent in the theater (that is, how popular it was) the firmer the memory. So I can recall Ferris Bueller’s Day Off with eidetic precision; Band of the Hand not so much. These films formed the catechism if you will of my Gen-X formation.

“Man is by his constitution a religious animal” says Edmund Burke, and while Kevin doesn’t say so directly, he describes movies and moviegoing in the language of ritual all over his book. Even before embarking on his movie-a-day-for-a-year adventure, he said he did what is proper before any ritual: fasting.

For the entire month of December I have engaged in a movie fast. Giving up movies is harder for me than abstaining from talking. I found myself calling my brother Chris, who teaches religion at Boston College, to see if there was some spiritual basis for a dispensation so I could watch It’s a Wonderful Life. No Dice.

Kevin clarifies to readers that his promise is not necessarily to see a different movie every day. In fact, in some cases as he says, “I want to explore the same film under different conditions.” How import are conditions? Does context matter? Consider: In 1977 I was a ten-year old boy in Anywhere, U.S.A. My parents took me to a theater in old downtown. This theater used to be an opera house in the 1800’s until in the 1930’s it converted to a movie house and by the 1950’s it was showing the kind of matinee films that most theaters did that would influence a certain George Lucas. That is, I wasn’t just watching Star Wars; I was watching Star Wars in a once-elegant theater with a continuity stretching back a century with an audience of similar backgrounds. In other words, I was being formed in a story-telling tradition, a common modern mythos with my fellow Americans, in addition to plain having a rollicking good time—a wonderful experience and a permanent memory.

The above thought no sooner occurred to me than I turned the page to read Kevin’s account of one of his favorite moviegoing experiences ever: Raiders of the Lost Ark. Read and try to recall the last time you felt this way about a movie:

From the outset, each and every person in that theater got sucked in, laughing at the jokes, thrilling at the stunts, hissing at the Nazis. No cynicism, no jaded boredom, several eruptions of spontaneous cheering. It was a one-hundred-and-fifteen-minute roller-coaster ride, the most wonderful experience I’d ever had in a movie theater, and I didn’t even have a date.

Events such as this are not just movies, but genuine adventures; the films themselves when removed from their context amount to nothing. The company, the mood, the venue—they’re as integral to a moviegoing memory as they are to a romantic meal, a thrilling concert, a great ball game…Life amounts to what we experience, not what we consume, but I’m afraid we’ve become a nation of consumers.

There is a famous scene in this movie where Indy is confronted with a swordsman expertly brandishing his weapon when Indy casually pulls out his revolver and shoots him. Ink has been spilled about how this is a violation of a proper hero’s code of conduct or even that it is ethically dubious. Maybe they are right, I don’t know. What I can tell you is that when that scene played in the same theater described earlier in June of 1981 I, my parents, and (as far as I could tell) everyone in the house roared with laughter for a solid minute. Now that’s how you subvert expectations!

But fast forward eighteen years and Kevin starting noticing something. “When the [MST3K] series ended in 1999, and I returned to the theaters, I didn’t like what I was seeing. Multiplexes were erupting around me like massive concrete sores. I began to notice fewer and fewer people happy as they left the theater, including me.” There was a change. It wasn’t like all good movies stopped being made but the change was vague but palpable. In the ‘80s and early ‘90s I would go to a movie almost weekly and didn’t really need to be concerned with what movie it was. Every now and then I wasted time and money on a stinker like Mannequin, but those were exceptions. If it was a film by a director in top form like Spielberg or Cameron, you just went, no questions asked. By the 2000s I went from weekly attendance to a handful of movies a year. Today, I might get to one or two a year; and then only after I researched it to make sure it wasn’t a waste of time or worse, an insult to intelligence. Murphy sums it well in his portentous comment about Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone:

It looked like a movie and sounded like a movie, and if you bought the theme cup it even tasted like a movie. My theory is that Harry Potter is a groundbreaking achievement for the future: a movie clone. It has all the outward appearances of a piece of entertainment without shouldering the onus of actually entertaining.

By the end of the year-long experiment Kevin tells us he managed to rekindle his love of movies—mostly by taking his entertainment into his own hands and relying on independent and foreign films to chase the bad taste of Hollywood schlock away. “I enjoy it more because I’m a smarter, pickier moviegoer.” However he also says he learned that “the cinema is not dead, not even close.” But we have to remember that this book is from 2002. So when Kevin says Star Wars: The Phantom Menace was “surely the loudest and dumbest films of this or any decade” he ain’t seen nuttin’ yet.

And here we are in 2024 and it’s “today” for another year. A lot has happened since Kevin’s book—Netflix, streaming services, and the last time we felt the smallest pang of nostalgia for any film made post-1997 was perhaps Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. However we can still imitate him by taking our entertainment consumption in our own hands, become “smarter and pickier” when it comes to movies where “money and time are on the line.” This is doubly important given that the rulers of the entertainment industries have made it a mission to actively attack everything you hold dear. However, what has been lost, perhaps irrevocably, is the ritual of moviegoing.